Oct 8

Political Notebook: Book examines intersection of the Holocaust and US LGBTQ movement

Matthew S. Bajko READ TIME: 7 MIN.

From the start of the Nazi persecution of homosexuals in 1933, the atrocities Adolph Hitler and his regime waged against LGBTQ Germans and others has impacted the LGBTQ community in America. Long before the Stonewall riots in New York City of 1969, the horrors unleashed by the Nazis were central to the fight for LGBTQ rights in the U.S.

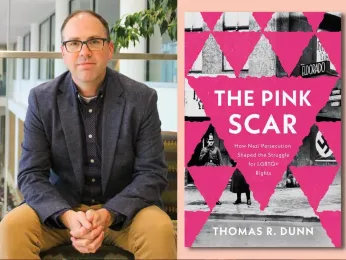

So argues Thomas R. Dunn, founder and director of the Queer Memory Project of Northern Colorado, in his new book “The Pink Scar: How Nazi Persecution Shaped the Struggle for LGBTQ+ Rights.” It will be released October 21 by Penn State University Press as the first book in its Troubling Democracy series.

“I am not writing about democracy, per se, but am happy to be part of that conversation,” said Dunn, 45, a gay man who is an associate professor of communication studies at Colorado State University. “A lot of the book has implications for how we think about democracy, historically and contemporarily.”

Speaking to the Bay Area Reporter by phone from Fort Collins, Colorado, where he lives, Dunn said the book grew out of the contention made by different historians and activists that most American LGBTQ people only learned about how homosexuals were persecuted during the Holocaust well after the conclusion of World War II. Yet, as he researched the topic, he discovered various archival records proving that not to be the case.

Practically from the start of the war, LGBTQ Americans had access to news reports about how German homosexuals were being rounded up. The coverage spoke about the pink triangles they were made to wear in the concentration camps to denote their being gay.

“I can pull up newspapers in middle America and see what they are talking about in 1935 and see the word homosexual in an article written on page three of a local newspaper. That was something hard to do as a scholar in the 1970s and 1980s in particular,” noted Dunn. “That is why we always have to go back to the literature. A lot more people knew about it than we might suspect.”

Looking at photographs from the very first White House picket by LGBTQ activists on April 17, 1965, Dunn noticed that some of the signs they carried referred to concerns that Cuba would institute labor camps for homosexuals similar to the Nazi regime. Yet, most remember the protest as being solely rooted in the U.S. Lavender Scare era when gays were drummed out of the federal government, he writes.

“Despite the great suffering and many laments of American homosexuals in the decades before 1965, it is remarkable that it was the sudden and provocative internment of Cuban homosexuals that broke through the organization’s trepidation about public protest and brought it, as later generations would demand, out of the closet and into the streets,” wrote Dunn.

He also documents how the Holocaust was used by pulp fiction authors for gay-based erotic stories in the 1960s and how the founders of the early gay rights group the Mattachine Foundation “explicitly framed their cause as necessary because of the suffering and persecution of homosexuals under Hitler” during the 1950s and early 1960s.

“More specifically, this book shows that the early lesbian and gay rights movement in the United States made remembering the persecution of homosexuals by the Nazis a central, animating, and indispensable part of their rhetoric and politics in the postwar era time and time again,” writes Dunn. “This claim counters much of our received wisdom about how early lesbian and gay communities in the United States understood – or did not understand – these events.”

Harvey Milk

He also began to notice how LGBTQ leaders in the U.S. talked about the Holocaust evolved over the decades. One chapter of the book is devoted to how the late gay San Francisco civic leader and politician Harvey Milk referred to that era of history and was often critical of the gay community in 1930s Germany for not being more forceful in fighting back against the Nazis. It is titled, “Lambs to the Slaughter: Harvey Milk, Memories of Shame, and the Myth of Homosexual Passivity, 1977-1979.”

Milk’s framing of the era fit into his larger themes of wanting to see more LGBTQ people come out publicly during a time when their rights were under attack across the U.S., noted Dunn. People like the late anti-gay crusaders Anita Bryant and John Briggs, a California legislator, led efforts to demonize queer people and rescind local anti-discrimination laws, or in the case of Briggs, enact a state law to ban them from teaching in public schools. Milk had defeated that effort in November 1978 just weeks prior to his assassination.

“I think Harvey Milk, above all things, was a strategic communicator. Everything that came out of his mouth was very intentional,” said Dunn. “He was very much focused on trying to make the lives of the people he represented safer and better, and that included not just the LGBTQ community but the people of San Francisco when he was elected.”

To Dunn, how Milk spoke of those impacted by the Holocaust did a disservice to their memory. At the same time, he understands why Milk used such rhetorical license in his speeches.

“I don’t think Harvey was particularly concerned about that. He was more concerned in the moment about how can we turn people out,” said Dunn, meaning to the ballot booth to vote down Briggs’ initiative. “The consequence from my perspective is it changes the way we think about these homosexuals who were persecuted by the Nazis for years and years thereafter. If I am someone who lived that life experience, I think it would have been deeply problematic for me. Harvey Milk’s concern was bigger than that and on what he could say at the moment to keep the ball moving forward.”

Gay rights leader Cleve Jones, a close confidante of Milk’s as he became a civic and elected leader in San Francisco, noted that Milk had come of age during World War II. Born in 1930 on Long Island in New York, Milk was 9 years old when the conflict began and 15 when it ended.

“As he was coming of age and coming to understand his sexuality, that nightmare was unfolding across the Atlantic Ocean from where he was living. There were Nazi sympathizer rallies very close to his home in New York,” noted Jones. “I think it is an interesting topic to raise during this current moment.”

Jones remembers Milk frequently speaking about the rise of fascism in Europe and often referring to the Holocaust.

“As a Jew, as a homosexual, he felt a deep connection to it,” noted Jones.

But he told the B.A.R. he doesn’t have a “specific recollection” of Milk questioning why gay Germans or others didn’t fight back about the Nazi repression.

“That was not an uncommon topic of discussion,” said Jones. “When you look at the newsreels and see adoring throngs of Germans and Austrians saluting the parades of Nazis and the Führer, their hateful messages were embraced. While there were scattered efforts of resistance, a great many people just acquiesced and did not fight back.”

With the rise today of authoritarian leaders in countries around the globe, and the anti-LGBTQ crusade the Trump administration has been waging since January, comparisons have been made to Hitler’s reign of terror during World War II. Fears have been particularly voiced about seeing transgender and gender-nonconforming Americans rounded up and jailed.

Last month, gay Congressmember Mark Takano (D-Riverside), who chairs the Congressional Equality Caucus, decried such comments being made by several of his Republican colleagues in the U.S. House.

“Now, Representatives Nancy Mace and Ronny Jackson are calling for transgender people to be locked up against their will and institutionalized. These comments are abhorrent and have no place in our society, especially coming from elected leaders,” stated Takano, referring to the South Carolina and Texas representatives, respectively. “This demonization of the transgender community must end. Speaker [Mike] Johnson and Republican leadership have a duty to reign in these extremist Members and put a stop to this vile, hateful rhetoric.”

What steps LGBTQ people and others should take in the face of such hostility echoes the debates waged on if they and others were too complacent during the German Reich.

“Yes, people have had conversations through the decades that have followed, wondering what would have happened if Jews and Romany people and communists and others had been better armed and what would have happened if they fought back with greater force. That is a question still relevant today,” said Jones.

Dunn, who grew up in the village of Warwick in New York State’s Hudson Valley, was named a 2020-23 Monfort Professor at his university. It came with research funding he used to work on his “Pink Scar” book.

The project presented a number of hurdles to him, one being his suffering through a severe case of shingles as he wrote the book. He was also raising his daughter, Ada, who was a 1-year-old at the time, with his husband, Craig.

Russia’s invasion into Ukraine upended his research trip to Poland and the Museum and Memorial at Bełżec. The COVID-19 pandemic also impacted his ability to travel to various archives, though he was able to access a lot of records and archival materials via online depositories or with the assistance of helpful staff members overseeing them, such as the LGBTQ-focused ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries.

He received a one-year extension in order to undertake the “extensive research travel” he needed to complete the project, as Dunn notes in his introductory section to the book.

He hopes his book assists with efforts to keep the memory of the Holocaust and the Nazi persecution of homosexuals in the minds of future generations of LGBTQ people and others. It is a history that should not be lost to time, said Dunn.

“We need to remind the younger generations. That knowledge continues to get lost as we lose the availability for people to speak about it firsthand,” said Dunn.

Web Extra: For more queer political news, be sure to check http://www.ebar.com Monday mornings for Political Notes, the notebook's online companion. This week's column reported on LGBTQ leaders’ reaction to the federal shutdown.

Keep abreast of the latest LGBTQ political news by following the Political Notebook on Threads @ https://www.threads.net/@matthewbajko and on Bluesky @ https://bsky.app/profile/politicalnotes.bsky.social .

Got a tip on LGBTQ politics? Call Matthew S. Bajko at (415) 829-8836 or email [email protected] .